More consumers hope to cut out self-gifting this year. They may be making a mistake.

Published in Slideshow World

Subscribe

More consumers hope to cut out self-gifting this year. They may be making a mistake.

Americans are heading into the first holiday season in years where buying less may be the first thing on their minds. And this year, gift lists may exclude one important person: you.

Stacker dug into Deloitte's 2024 holiday retail survey to explore the psychology behind Americans' reluctance to self-gift this year.

In the modern era, holiday gifting includes a practice that may seem rooted in consumerism—giving ourselves gifts. However, "self-gifting," psychologists say, carries its own importance. It's one consumers intend to cut back on or eliminate entirely this holiday shopping season, according to Deloitte's 2024 holiday retail survey of over 4,000 U.S. consumers.

We've all done it. With hard-to-resist Black Friday deals and hypertargeted advertising, it can be difficult to resist shopping for yourself when doing so for others. Meanwhile, the cost of goods and services has risen faster than usual every year since 2021, when post-COVID-19 pandemic inflation took root in the U.S. economy and altered how we consume.

Even so, Americans expect to spend more on gifts this holiday than in the previous five years. Deloitte found that the average person anticipates spending $1,778 this year, a 19% increase from 2019, when the average expected spend was $1,496. Baked into that figure are consumers' expectations of higher prices this season, according to Deloitte.

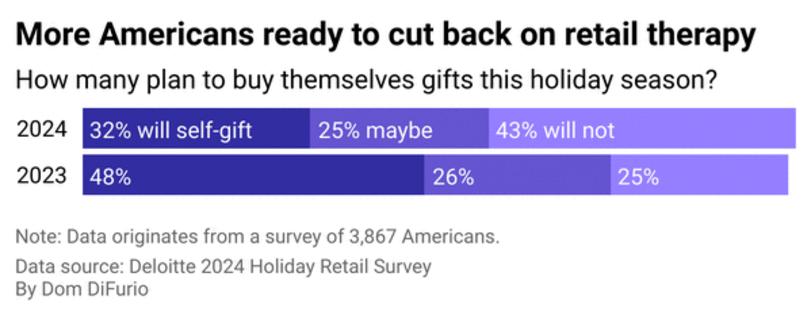

In response, some Americans are signaling they may do less for themselves. About 1 in 3 consumers intend to self-gift this year, down from almost half of all consumers last year, Deloitte found. At least 2 in 5 (43%) won't spend on themselves at all, up from 25% last year.

Today, the appeal of giving gifts around winter holidays is nearly universal. The holidays have long been an occasion to show our love for others in the exchange of gifts. Though giving gifts may have emerged from the biblical story of the three wise men, Christmas celebrations were among the first to lean into a commercialized version of the winter holidays. Other religious traditions like the Jewish celebration of Hanukkah have evolved to include gifting as a part of its observance over the winter holiday. Even workplace culture has adopted gifting as a way to foster connections and lift moods with traditions like Secret Santa.

This holiday season, though, our modern treat-yourself-culture could be on pause for many Americans.

Visit thestacker.com for similar lists and stories.

More Americans prepared to remove themselves from holiday gift lists

Dr. Steve Westberg, a professor of marketing and consumer psychology at the University of Southern California, suggests that the uptick in surveyed adults who say they hope to scale back self-gifting this year may be due to consumer pessimism and financial concern.

Faced with more limited options during the pandemic years, Americans bestowed themselves with material goods—some out of practical necessity, others not. Over the 2020 and 2021 holiday seasons, Americans hunkered down at home to avoid catching or spreading the latest COVID-19 variant. They bought lots of furniture, electronics, and other items in lieu of spending on travel, outings, and live events.

In 2022 and 2023, consumers embarked on so-called "revenge travel" to catch up on international and domestic trips. They attended the live music and sporting events they had missed out on.

Today, there are signs that all of that spending is beginning to cause stress for the typical American consumer as prices remain painfully high. Americans' total amount of credit card debt is at an all-time high, and default rates for vehicle loans and credit cards are rising. In almost every major poll leading up to the 2024 presidential election, the economy and inflation were consistently the top issues driving voters to the polls.

However, as consumers pull back, there's evidence that self-gifting can positively impact personal well-being. Jacqueline Rifkin, an assistant marketing and management communications professor at Cornell University, describes the practice as a way to self-regulate emotions.

Self-gifting can express positive emotions in a way we may recognize as a celebration.

"You just got a promotion, or you won some big award, you're feeling good, and you want to extend or amplify those good feelings. You can use self-gifting to achieve that," Rifkin told Stacker.

Self-gifting can also be a way to deal with negative emotions. Rifkin published research in the Journal of Consumer Research on self-gifting, which revealed that people were least likely to gift things to themselves when under stress or feeling constrained—even though self-gifting can help us regulate during stressful moments.

"If you're going through a rough time … you can use self-gifting to pick yourself back up. One of the colloquial ways we think about this is 'retail therapy,'" Rifkin said.

Can self-gifting and retail therapy veer into wasteful self-indulgence? Potentially, according to Westberg, who says the reasons we self-gift are similar to those that drive compulsive shopping habits. The act generates a positive emotional response. There's an important distinction, however, that experts draw between the two.

Westberg and Rifkin agree that self-gifting stands out from other forms of shopping in that it incorporates intentionality. "You could define self-gifting as being a little more thoughtful in your choice," Westberg explained.

Consumer advocates suggest that shoppers looking to cut back on spending create guardrails to help them shop more intentionally. Removing credit card information from our web browser's autofill function or delaying the impulse to "buy now" and creating a wish list instead can elongate the purchase process. Putting space between the initial urge to buy and the purchase can be revealing, too: It clarifies what's really meaningful and worthy enough to justify buying.

For others, like Westberg, shopping satisfaction is derived from researching items to self-gift in the future. Westberg's initial inclination when it comes to self-gifting, like many of us, is to reward himself with some kind of "big ticket" item.

"On the other hand, I don't know that I'll ever actually do that because once I have it, the anticipation aspect is going to go away," Westberg said. "So while I do think about self-gifting myself a car … I get a lot of enjoyment [from] doing the research. … [It's] the thoughtfulness that I can put into it rather than having the physical thing."

According to Rifkin, our reluctance to give ourselves gifts isn't always born of financial constraints but also a belief that giving ourselves something won't actually make us feel better, even though it can. She advises consumers to remember that gifts can take on different forms this holiday season, and many of them don't cost a thing.

"It's this intentional behavior that we engage in. It's something you do, you do it on purpose, and you do it for yourself," Rifkin said. "Could it be going for a walk around the block? Absolutely. Could it be dusting off a book that you hadn't read in a while and spending an hour reading it? Yes."

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Kristen Wegrzyn.

Comments