UC San Diego awarded grant that could help transform organ transplants

Published in News & Features

SAN DIEGO — Researchers at the University of California, San Diego are among five groups nationwide selected to share $176.8 million in grant funding to explore replicating vital organs, an approach that, if successful, would revolutionize transplant surgery, making organ failure vastly more survivable.

Announced Monday by the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H, the awards are part of the Personalized Regenerative Immunocompetent Nanotechnology Tissue program or PRINT, which seeks to use state-of-the-art bioprinting methods to create “on-demand human organs that do not require immunosuppressive drugs.”

ARPA-H, created in 2022 with a $1 billion congressional appropriation and signed into law by President Joe Biden, is modeled on a similar federal agency, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, that has long pursued leap-forward breakthroughs by funding big, but uncertain ideas. Just as DARPA’s long-term research funding over many decades led to major gains, including ARPANET, the decentralized communications system that evolved into the Internet, the idea is to fund goals located slightly over the horizon.

The health innovation agency’s first program, announced in 2023, funds research on tissue regeneration therapies to treat osteoarthritis. Similar efforts in obstetrics, robotic surgery, cancer screening and indoor air quality have been announced. Programs are also being launched to spur innovation in cancer research, including a $142 million precision treatment program that ARPA-H announced in 2025. UCSD researchers, along with teams at nine other institutions, will each receive up to $25 million over six years, working to develop biomarkers that can “anticipate tumor evolution” and predict drug response.”

A nearly identical amount is to be allocated for PRINT, with UCSD receiving up to $25.8 million over five years to “develop a scalable, patient-specific bioprinted liver using adult stem cells. This liver will be tailored to an individual’s unique anatomy and physiology, without the need for donor tissue or immunosuppressants, ensuring long-term functionality and integration.”

Three other U.S. institutions have been chosen to pursue essentially the same goal: Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Wyss Institute in Boston and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Wake Forest University in North Carolina is tasked with creating viable kidney tissue to “augment renal function in patients suffering from kidney disease.”

In the ARPA-H grant announcement, PRINT project manager Ryan Spitler made it clear that this is a moonshot.

“What we are trying to do with PRINT is extraordinarily hard,” Spitler said. “It requires major breakthroughs in cell manufacturing, bioreactor design and 3D printing technology to reliably build organs that function like the real thing.”

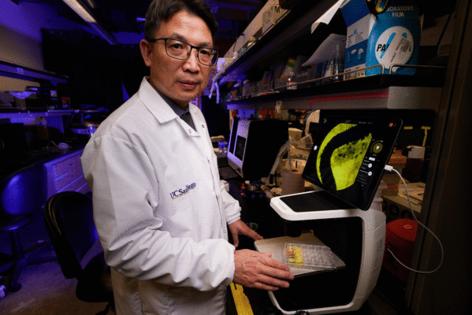

In San Diego, that weighty gauntlet will be taken up by a team led by UCSD bioengineer Shaochen Chen, a professor in the university’s Jacobs School of Engineering. The task is so complicated that it will span biology, imaging, surgery and artificial intelligence.

At the center is an innovative type of 3D printing for which Chen, starting at the University of Texas, has been a pioneer. He began building machines that use projected light to more rapidly print tissue made from induced pluripotent stem cells, a basic type of human cell that research has shown can be coaxed into specialization. Chen’s extensive curriculum vitae states that his research was the first to print multicellular liver tissue using the techniques he has developed, with the help of others, over 25 years.

Most bioprinting efforts, Chen noted in a recent interview, involve extrusion, squirting a mixture of cells and a material called biogel through a tiny nozzle, creating a stream of material that can be built up layer upon layer, under computer guidance and following a digital model of the object’s design. It’s very similar to the technique now commonly used with commercially available 3D printers that use melted plastic filament to create objects from digital files.

But Chen’s method works differently.

“The difference between us and others who do extrusion printing is that we print the whole page at the same time, and that’s truly 10,000 times faster than what they do,” Chen said.

He worked with Texas Instruments to adapt digital light processing technology used in digital movie projectors to instead expose fields of bioink simultaneously. As with photolithography, the technique used to create integrated circuits on silicon wafers, the method, often called optical projection bioprinting, casts a pattern of light and dark shapes across the entire printing field. Areas where light is let through cause the polymer at those locations to harden, while areas kept in the dark stay fluid.

The exposed areas provide structure, functioning like a scaffold that holds layers of cells in desired locations. And, just like extrusion printing, this process can be built up by adding additional layers. Chen’s team has found a way to make the connections between successive layers continuous.

In the unexposed areas, the biogel stem cell mixture remains, and this is where the potential for creating a functional human liver resides.

“The gel naturally degrades as the cells release an enzyme, their own natural cell matrix,” Chen said. “By day five, day 10, the gel will be gone, and then you end up with all of the liver cells connected with cell matrix.”

UCSD has already developed techniques that can make small sections of liver tissue that include relatively large-scale blood vessels. But the challenge will be getting even more fine-grained. In order to survive long-term, liver cells must be no more than 300 microns, the thickness of three human hairs, away from a blood vessel.

“If they are too far away from the blood flow, these cells just don’t get nutrition, and they die,” Chen said. “That’s the grand challenge.”

At the current level, he said, the technology is capable of producing the major infrastructure, the highways serving a city. But building those secondary roads branching down to the city streets and lanes that serve individual homes, that’s the part still to be delivered.

“That’s where we need help from biology,” Chen said. “Biologists actually learn how to build vascular vessels through biological pathways.”

UCSD will collaborate with Allele Biotechnology, a San Diego biotechnology company with expertise in producing stem cells and inducing them to transform, to produce the different cell types that the project will require. Co-investigators, according to a statement from UCSD, include Bernd Schnabl, Gabriel Schnickel, David Berry, Claude Sirlin and Ahmed El Kaffas at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and Padmini Rangamani and Rose Yu at UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

Schnabl, a gastroenterologist and physician scientist at UCSD whose lab studies the progression of chronic liver disease at the molecular level, noted that building the proper infrastructure around liver cells is not just about plumbing in functional blood vessels. The liver, he noted, also produces bile, a substance that is vital to many bodily functions, which moves through special ducts.

“Bile has a lot of functions, first of all to support our digestion,” Schnabl said. “It supports the immune system and other functions like glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, in our entire body.

“So this adds an additional layer to this challenge.”

Getting various cell types to connect with each other and perform specific functions, he noted, is likely to involve additional work with Allele, making subtle adjustments to how blank-slate pluripotent stem cells are induced to turn the cell types that are needed to pull the project off.

The liver, he noted, is a very complex organ, performing what medical literature describes as more than 500 different functions. But, the possibility of printing a human liver, one that would be made from a person’s own stem cells, well, that is enough to get anyone dreaming. After all, an estimated 12,000 people per year die due to the unavailability of donor livers.

“We have so many patients on the liver transplant list for whom we do not have a sufficient amount of organs available,” Schnabl said. “Creating a liver to replace an old organ for a patient who needs it, we are very enthusiastic about that idea.”

Is five years, the length of the ARPA-H grant, enough time to cover the distance from where the liver-printing technology is today to a human-sized liver with all of the necessary features to make it function properly?

Chen says he believes it is. Plans are to first print a small liver, perhaps five millimeters, that can be transplanted into rats. If that first step is successful, then a full-size 15-centimeter organ would be tested in pigs. He said that, with focus and good funding, being ready for a human trial in five years is possible.

_____

©2026 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments